Paradoxical practice #1, detailed last week as I’ve come to know it, was “don’t care.” Clarified, the practice of “don’t care” means to not be attached to what reality will always deem inevitable when it comes to how things turn out. How anything turns out. Paradoxical Practice #1 means we humans, as fully integrated beings within nature, are not meant to care about how things turn out. Things will always turn out the way they turn out regardless of our desire to have things turn out the way WE want them to turn out. In World Series parlance, nature always bats last. We can “want” all we want; we are free to do just that. But to the degree of the strength of our attachement to the wanting, we invite suffering into our lives when reality differs from the ideal we established in our minds.

It’s a heavy lift, this particular practice. But not the heaviest.

The first Tenet of the Order of Zen Peacemakers, founded by Roshi Tetsugan Bernie Glassman, is I will embody Not Knowing, thereby giving up fixed ideas.

Not Knowing; Giving up fixed ideas. THAT’S all about nurturing a healthy dose of Doubt. Zen teaches Doubt. And we in America had one of the grandest Zen Masters of Doubt who EVER lived!

This one I can frame in a way I think everyone will identify with, especially those of us in America, in 2024 America, in “presidential election year” America.

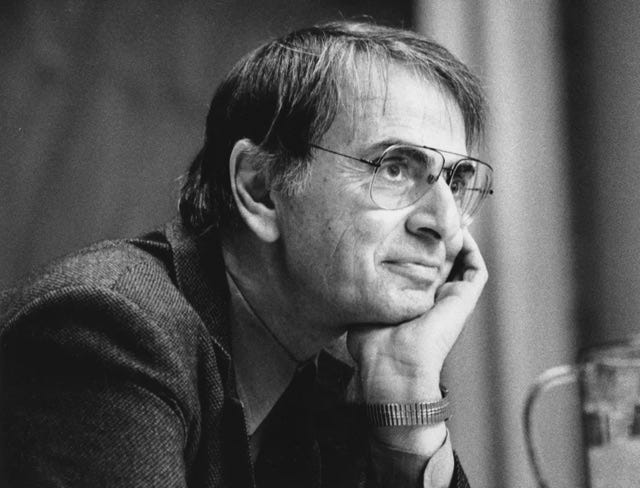

As I’ve mentioned within the context of these paradoxical practices, I’ve learned from many teachers and masters who devoted their entire lives to these essential, existential questions. For the Paradoxical Practice of Doubt, I turned to one of America’s own, great Zen masters—the late, GREAT, Dr. Carl Sagan!

Needing a Candle for the Dark

The context:

As I bear witness to the national dialogue on our presidential candidates, and as I both observe and listen to those who have clearly “picked their winner,” no matter which side of the ideological spectrum they may fall, the thing that disturbs me the most, that worries me the most, that makes me fearful and nervous about our future as a democracy, is when I hear American citizens say “I don’t care what you say, I don’t care about facts, I don’t care about any evidence you may have to the contrary, you’re not going to make me change my mind.” As a former science teacher, it’s hard for me to understand that way of thinking. But I do know this—THAT is exactly how a democracy dies should that mindset spread either to a majority of the voting republic (not ever likely btw), OR a candidate is able to assume power (I see you Electoral College) who knows how to wield this toxic and destructive power over a base of voters. America wasn’t founded upon those who wielded blind faith and allegiance to a single person, personality, movement, or ideology. America was founded by people who knew not only how, but the importance of being able, to question. American democracy and politics demands we be persuadable. It’s been said politics is about the art of negotiation. One cannot negotiate with another who refuses to be persuadable; who refuses to doubt their own beliefs when doing so might result in something better for everyone.

I picked the presidential election to illustrate the Practice of Doubt because it is such an “in our face” example of stubborn, cultish behavior. But we all know people who fit into the same category of stubborness, politics completely aside. And if we are honest with ourselves, even we fall into the category at times with our own cherished beliefs—be they religious, secular, social, environmental, or intellectual. We are human, and this defines to a degree who and what humans are.

To help ground myself into this mindset, I went back this week to a book that is in my top five books OF ALL TIME! I read it initially because of my love of science and deep respect and admiration for the author; I used it when I taught thousands of science students; and I fell in love with it due to its beautifully-crafted prose, sound logic, historical significance, and utter brilliance:

I bought it roughly when it initially came out in paperback back in the late 90’s. I pick it up every now and then, like a warm comforter, to luxuriate in Sagan’s lucidity, grounded wisdom, beautiful use of language, practical application from history’s lessons, and his own staunch faith in science as “a candle in the dark.” Two chapters in this amazing book speak directly to the value and necessity of Doubt in a democracy and as a personal practice: Chapter 17 is titled “The Marriage of Skepticism and Wonder;” and the last in the book, Chapter 25, is titled “Real Patriots Ask Questions.” Though published in 1995, the events of the current day not only make Sagan a prescient prognosticator and champion of true democracy, but also a wise sage and zen master whom we forget or ignore at our great peril. Sagan, in this book, in addition to exploring the pitfalls of anti- and/or pseudo-scientific thinking in everyday matters, tells us over and over again we’ve been here before as a society on the whole. More than once, in fact. And we know how to get out of this mess that certain people, with malevolent influence, have led us into. But, it involves a choice—and sadly, a vote. And it involves humility—humility being the underlying characteristic to the practice of healthy Doubt.

The Marriage of Skepticism and Wonder

Turning to his own words now (if you are not familiar with Sagan’s genius use of language, you’ll catch only a glimpse of it here), here is what Zen Master Carl teaches us. Please keep in mind as you read the examples you yourself have of those among us who hold on to a certain set of beliefs so strongly, that they say they can never be persuaded to believe otherwise no matter the evidence that might be staring them right in their blind-faithed eyeballs (the greatest challenge is to reflect upon your own self and your own cherished beliefs):

When explaining why people hold on to their beliefs, Sagan writes:

“All of us cherish our beliefs. They are, to a degree, self-defining. When someone comes along and challenges our belief system as insufficiently well-based—or who, like Socrates, merely asks embarrassing questions that we haven’t thought of, or demonstrates that we’ve swept key underlying assumptions under the rug—it becomes much more than a search for knowledge. It feels like a personal assault.” (p. 297)

This can serve to “dig the person deeper” into the hole of belief despite obvious facts to the contrary. It explains why it is not only impossible to “argue” with such people, but that it actually causes harm. Questioning or giving up our beliefs means giving up a part of our identity. When confronted, we’ll tend to dig in even deeper, eg: “I don’t care what you say or show me, you’ll never convince me otherwise.” THIS is what worries me as I see my fellow MAGA-oriented citizens, or even dogmatic blue-voting ones, and ask myself who will we be come November 6, 2024?

Sagan also anticipates what would be the appropriate argument for doubting even science.

“If you’re open to the point of gullibility and have not a microgram of skeptical sense in you, then you cannot distinguish the promising ideas from the worthless ones. Uncritically accepting every proffered notion, idea, and hypothesis is tantamount to knowing nothing. Ideas contradict one another; only through skeptical scrutiny can we decide among them. Some ideas really are better than others.” (p. 305)

“As I’ve tried to stress, at the heart of science is an essential balance between two seemingly contradictory attitudes—an openness to new ideas, no matter how bizarre or counterintuitive, and the most ruthlessly skeptical scrutiny of all ideas, old and new. This is how deep truths are winnowed from deep nonsense.” (p. 304)

“The judicious mix of these two modes of thought is central to the success of science [and democracies, I would add. ~kert]. Good scientists [and citizens] do both. On their own, talking to themselves, they churn up many new ideas, and criticize them systematically. Most of the ideas never make it to the outside world. Only those that pass a rigorous self-filtration make it out to be criticized by the rest of the scientific community.” (p. 305)

Science demands Doubt. This is why one best defines Science not as a set of facts but as a way of systematically thinking about the world. Science builds in an intentional process of “self-filtering, self-correcting” doubt. It’s called: the scientific method.

Distinguish this with those who NEVER “self-filter” their beliefs let alone allow others to do it for them in a systematically rigorous way. They even go so far as to denigrate, demean, lie about, and cause great harm to the dedicated scientists, and their science, who bring sometimes very hard, difficult and unpopular news to the populace (here I’m thinking of the world-renowned immunologist Dr. Anthony Fauci, former esteemed director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and how he has been unjustly demonized by the political right; heck, let’s even count the threatened TV meteorologists for merely reporting on the weather should they also mention the effects of climate change!).

Sagan ends Chapter 17 with this:

“Both skepticism and wonder are skills that need honing and practice. Their harmonious marriage within the mind of every school child ought to be a principal goal of public education. I’d love to see such a domestic felicity portrayed in the media, television especially: a community of people really working the mix—full of wonder, generously open to every notion, dismissing nothing except for good reason, but at the same time, and as second nature, demanding stringent standards of evidence—and these standards applied with at least as much rigor to what they hold dear as to what they are tempted to reject with impunity.” (p. 306)

How do you know you know what you know?

Sagan’s wish IS one of our main missions as teachers—to provide students not only with knowledge and skills, but also to nurture and develop a “way of thinking” that allows for an understanding of how the world works, and our place in it, based upon systematic, rational, critical thought—in other words, the development of healthy Doubt. Along with the “what’s” (ie math, history, biology, reading, writing, etc), I taught the how. Teaching students how to think is critical in the development of an informed citizenry especially in a democracy. If I were to ask any of my former students the question directly above this paragraph, I would want them to say something like the following:

“I know because I put great effort into my thinking; I looked critically at all the evidence available to me, I considered thoughtfully and seriously all viewpoints both for and against my own position, I looked at things as objectively and dispassionately as I could so that I was not impeded by irrational emotion, or ad-hominem argument or attack, or persuaded by an outsized and arrogant person/personality; and made my conclusions based upon a rational, evidenced-based approach to thinking. If that prompted me to change my position or even my cherished beliefs, then I had to change my position and cherished beliefs—because they were wrong.”

If my students answered like that, I’d die a very happy retired science teacher! Contrast that with “because he told me to think that way, and that’s good enough for me” and you see the stark differences that distinguish our citizenry right now.

For me, this is the paradoxical practice of Doubt. It’s paradoxical because we typically don’t want to question our own beliefs—let alone the ones we hold most passionately. I try to do this; I try to make this form of Doubt my practice. If I look at or judge another for their stubbornly held beliefs, that prompts me (most of the time, not always; it’s my practice!) to ask myself “so why exactly is it that I think my beliefs are better, or more accurate, or “The Truth?” If I can cite no evidence, based upon established, unemotional, dispassionate facts, then my beliefs, themselves, are built on sand and not worth the material they are made of.

Real Patriots Ask Questions

This last chapter from The Demon-Haunted World should, I believe, be hard-copied and given to every school child, American citizen, and immigrant seeking asylum and citizenship in our country. Sagan defined for us today, here in 2024, way back almost 30 years ago in 1995, how a meaningful and serious democratic citizenry should function—should they choose, that is, to keep their democracy.

“It is not the function of our government to keep the citizen from falling into error; it is the function of the citizen to keep the government from falling into error.”

~ U.S. Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Jackson quoted by Sagan as the preface to Chapter 25. (Jackson’s words were written in 1950!).

“Even a casual scrutiny of history reveals that we humans have a sad tendency to make the same mistakes again and again. We’re afraid of strangers or anybody who’s a little different from us. When we get scared, we start pushing people around. We have readily accessible buttons that release powerful emotions when presssed. We can be manipulated into utter senselessness by clever politicians. Give us the right kind of leader and, like the most suggestible subjects of the hypnotherapists, we’ll gladly do just about anything he wants—even things we know to be wrong. The framers of the Constitution were students of history. In recognition of the human condition, they sought to invent a means that would keep us free in spite of ourselves.” (p. 424)

The “means” they invented, to “keep us free in spite of ourselves,” were the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. In this chapter, Sagan goes to great lengths to share some of Thomas Jefferson’s thinking as one of our nation’s principal Founding Fathers. [Important aside: I’m intentionally laying off to the side the facts of Jefferson’s own serious moral failings, to say nothing of the fact our “Founding Fathers” freely stole lands that were already under sovereign rule from a multitude of Indigenous Nations. That I do this, and that Sagan quotes from Jefferson, should not diminish the importance of what was thought about and discussed at “our Nation’s” founding by people who championed democratic rule as opposed to monarchical, dictatorial, authoritarian, despotic, or fascistic rule.]

“Jefferson was a student of history….” History taught him that the rich and the powerful will steal and oppress if given half a chance. [Jefferson] taught that every government degenerates when it is left to the rulers alone, because rulers—by the very act of ruling—misuse the public trust. The people themselves, he said, are the only prudent repository of power.” (p. 426)

“[Jefferson] believed that the habit of skepticism is an essential prerequisite for responsible citizenship. He argued that the cost of education is trivial compared to the cost of ignorance, of leaving the government to the wolves [ie malevolent rulers].” (p. 427)

More from Sagan:

“Part of the duty of citizenship is not to be intimidated into conformity. I wish that the oath of citizenship taken by recent immigrants, and the pledge that students routinely recite, included something like “I promise to question everything my leaders tell me. I promise to use my critical faculties. I promise to develop my independence of thought. I promise to educate myself so I can make my own judgements.” (p. 427-8)

In a very real way, the citizens who have bought in to the MAGA message “hook, line, and sinker,” with such rabid passion, have helped me to not only practice my compassion, but to also insure I’ve done the necessary work I need to do to question my own staunchly held beliefs. Beliefs I want to believe are factual and true. “How do you know you know what you know?” is the key question within the practice of Doubt. My teachers for this abound—they wear red hats and attend incoherent political rallies; they yell with open mouths, closed minds, and hard hearts; they believe in alternative facts; they ridicule science and scientists and scientific findings; they think the weather is controlled by people in the opposite party; they thumb their noses at lawfully decided judicial outcomes/findings; they believe a peaceful community of immigrants steal pets and roast them for dinner; they loudly repeat lies as if they were gospel; they are like sheep following a wolf with blind-faith that that wolf, and only that wolf, can solve their problems—because the wolf himself told them to believe only this.

I have compassion for these, my teachers but, importantly, only to a degree! To a degree, they are victims of a ruthless, fascist leader. Sagan cautions us about this as a result of lazy or non-thinking. But they’ve also made a choice; they are fully responsible for not using their minds as America and patriotic citizenship demands. When they slip all too easily into explicit forms of racism, bigotry, and hatred, my compassion evaporates—replaced to a large degree by revulsion, contempt, and utter disbelief. Regardless of it all and the political outcome, come November 6 and beyond, we will remain “fellow citizens.” Maybe. We’re gonna need lot’s of Sagan’s candles.

I’ll do my part. I will gift forgiveness while honoring and trusting the full extent of the law and the ideals of “justice for all” as articulated in our Bill of Rights. But most importantly, to bring this back to the Paradoxical Practice that it is, I will continue to doubt my own beliefs, to question what and why I know what I think I know, for the purpose of leading us all down a “more perfect union” of, by, and for the people. All people. Even those who wear different colored skin, think differently, love differently, worship differently, speak differently, and vote differently. All while living and promoting the natural laws of kindness, generosity, compassion, and love. Doubt does not have to be a heavy lift—it can be a joyful practice when done with a sense of awe and wonder. And the active choice of curiosity. Done authentically, it is a humble and vulnerable practice.

I trust you see how this practice extends beyond mere politics. Doubt is a healthy way to be in the world when one is tempted to rely solely upon beliefs. When we’ve distanced ourselves by time, isolation, religious or political dogma, tribalism, lazy thinking, or convenience from the hard and vulnerable work of critical self-reflection and analysis, we’ve sold our souls to the dark demons in Sagan’s Demon-Haunted World.

The true test of the efficacy of Doubt as a practice for me is if I can humbly admit that I am wrong, and then have the inner fortitude and courage to change my decisions or paths; and then champion what has come to light despite the fact I may have, prior, passionately lived otherwise. I want to be persuadable. We all should be persuadable. It’s a requirement for a healthy community and nation.

THAT is the lit Candle that is always there for our taking.

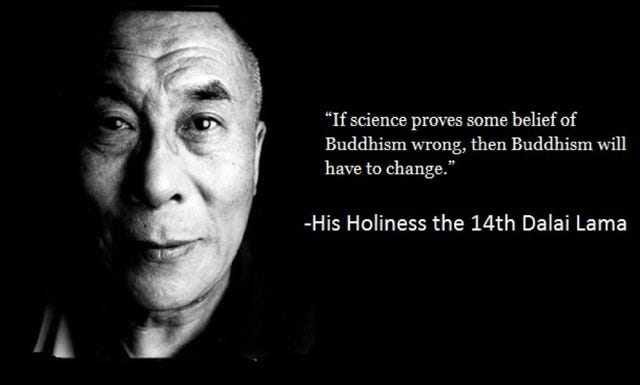

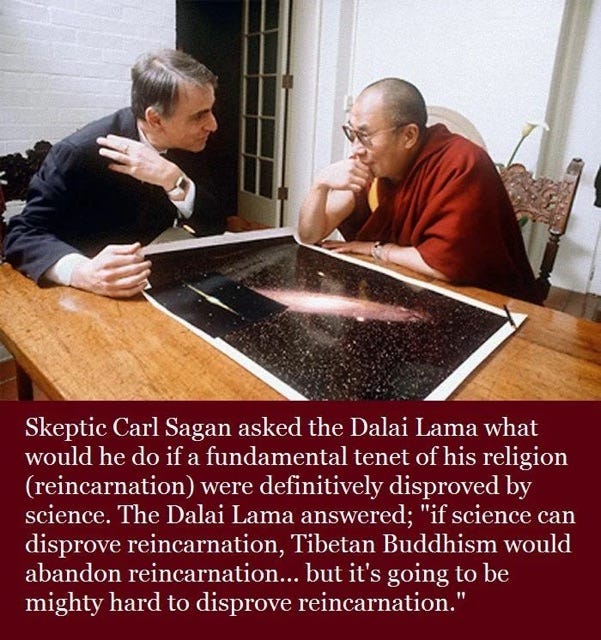

Carl Sagan and His Holiness the XIV Dalai Lama met personally and engaged, over the years, in open-hearted dialogue on the merits of science and the mystery of spirit.

So, don’t take just my word that Carl Sagan is one of our best Zen Masters of the recent age; take it from a still-living saint, himself a forced migrant from his homeland from an oppressive ruling state, who should know best and who also models for us what a healthy propensity for Doubt should look like:

.

In Sagan’s practical vision of democracy, the Dalai Lama would make an ideal American citizen.

Democracy Dies in the Dark

It is only fitting that Carl Sagan gets “the last words.” They come in the final paragraph of The Demon-Haunted World (the last book, btw, he ever published), and serve as a fitting epitaph and homage to critical thinking in a tenuous political era; they are both a prayer and a plea; and they are both a promise and a warning. In 1995, Carl Sagan, an unheralded Master of Zen, wrote these words for our eyes and minds and hearts here in 2024. Collectively, they are the Candle in the Dark:

“Education on the value of free speech and the other freedoms reserved by the Bill of Rights, about what happens when you don’t have them, and about how to exercise and protect them, should be an essential prerequisite for being an American citizen—or indeed a citizen of any nation, the more so to the degree that such rights remain unprotected. If we can’t think for ourselves, if we’re unwilling to question authority, then we’re just putty in the hands of those in power. But if the citizens are educated and form their own opinions, then those in power work for us. In every country, we should be teaching our children the scientific method and the reasons for the Bill of Rights. With it comes a certain decency, humility, and community spirit. In the demon-haunted world that we inhabit by virtue of being human, this may be all that stands between us and the enveloping darkness.”

Carl Sagan (b. Nov. 9, 1934; d. Dec. 20, 1996)

May he rest in peace but may his spirit live on. Thank you Carl.

Live, Laugh, and Love—with Clear Eyes and a Full Heart.

Always and Ubuntu,

~ kert

Ahimsa!

🙏🏼

Sagan, Carl. The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark. Ballantine Books, New York. 1995.

I will need to check out this Sagan book. Although I am aware of him and his contributions to society, I have never read his work. Thanks for the recommendation.