Final post of the month—another Dad post written in January before his death in March. It is presented unedited as it was first written.

In baseball terms, these days of late July and into August are also known as “the dog days of summer.” Even though the moniker has nothing to do with dogs or baseball (it’s an ancient Greek phrase associated with the constellations present in the Grecian night sky during the hottest days of the year!). So as good a time as any to send this particular reflection. FYI: the Mariners are in fourth place in their division—not the season they had hoped to have to date.

And btw: this is my 100th substack post. Thank you for hanging in there with me—even through the dog days of two summers.

Preface:

Amidst all the Dad posts in this Substack, I’ve embedded a few different “series” that gather themselves into specific themes: “Cooking a Life: From the Farm” are stories that come directly from Dad’s life, our lives, living on a hop farm—stories that highlight what I call “ingredients” that went into the making of our lives with Dad being the Tenzo, or head chef; “Dying Wiser” are the Elderings from Dad, often through a literature or poetry lens, as we learn for ourselves how to enter into our own aging, elderhood, and dying days a little wiser for having learned how Dad is navigating all of his.

There are more ingredients off the farm and more Elderings for dying wiser to come; with THIS post, I am starting a new mini-series called “Dad as a dad.” In all the world, there are currently only three people who know what it was like growing up with Dad as a dad. And each of us, Trevor, Clary, and I, experienced Dad in our own unique ways. Many of you know there were two more individuals who had similar experiences but both our sister Toni, and our brother Terry, took to their own graves any of the additional stories they didn’t share with us prior to their own deaths. Those stories, their stories, now lost to eternity unless they’ve been told. A good lesson, that.

Our stories, and the telling of the stories to our children, remain important. It’s already been said here: “A person might be fated to die twice in their lives—when they physically die, and again when they are forgotten (or when the stories held by their survivors are no longer shared). I don’t want Dad to die the second time even after he does the first, which he is obligated by life to do. So, I write.

There is a lot to share about who Dad was as a dad—so over the next few months, I’ll explore that “out loud” with you all. It should bring up some wonderful and nostalgic memories. But, know this:

What I am about to share about Dad, as a dad, is highly personal and idiosyncratic. This is my experience only; even though we grew up in the same house, for at least the formative years of our lives, Trevor’s and Clary’s experience of Dad as their dad is, by definition, different. They may have experienced Dad altogether differently—but because Dad was nothing if not genuine and authentic, to a great degree this is doubtful. I’m certain our experiences were very similar even given whatever differences do and should exist. Nonetheless, what I share here is my personal experience so I own it all—even the memories that are incomplete or faulty. Still, they are my memories, and I’m thankful I have them. Because…

Dad was a GREAT dad, but he wasn’t like other dads.

Okay, but first: the cinematic connection:

Don’t think it odd I’m starting this series in the following way. Rather, know this particular narrative has been locked within me for a very long time and it felt right to me to share it here with you all now.

The year 1989 brought to my life two of my all-time favorite movies. One, a story of a youthful and charismatic English teacher newly hired at a stodgy, all-boys prep boarding school who, in turn, and through both comedy and tragedy, changes the life course of each and every one of “his lads,” through poetry of all things (can you name the movie***?); the other about a corn farmer from Iowa who begins to hear voices in his corn fields that convinces him to plow under a portion of his crop to make way for, of all things, a baseball diamond; and then goes on an epic quest in search of something that makes no sense to him and that he can’t even figure out what he’s looking for until the last five minutes of the movie.

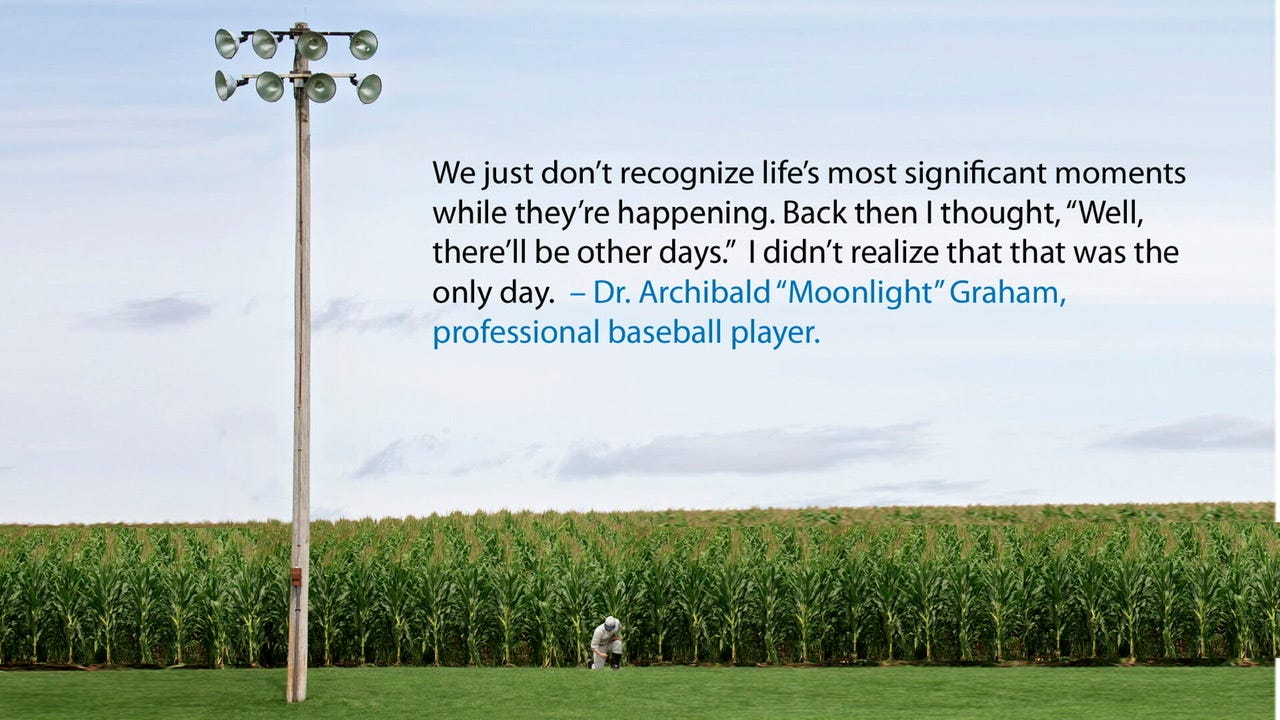

It’s that second movie, about that Iowa corn farmer, the guy with the voices in his head who begins to see ghosts after he built, in the middle of his farm acreage, a “Field of Dreams,” that I want to speak to in the context of my Dad.

***WARNING!*** If you haven’t seen Field of Dreams yet, (and why the HELL haven’t you??? It debuted 34 bloody years ago!!!) you might want to stop reading this post, right here and right now. “Cuz there be major SPOILERS ahead! I highly recommend you find the movie that is streaming currently in many places, including YouTube, and rent it to watch it. Buy it if you can. If you are a son, or know a son, or love a son, or think you know a son of someone, you’ll thank me later. Liking baseball is secondary and almost irrelevant.

Or come on over to my house—I have it on DVD! We’ll watch it together with Dad.

Bring popcorn. Better yet, bring whole kernal popcorn-ready corn that we will, together, pop on the stove a-la Dad-style! And remember also to bring a dozen wholewheat blueberry muffins (vegan please). And a gallon of iced oatmilk sugar-free vanilla lattes. You’ll feel at home then and get to experience a bit of what life at Club Med: Lenseigne campus is like for Dad.

Oh, and bring one cookie (vegan again please!). That’s how we’ll bribe Dad into watching a two-hour movie. With a potty-break intermission. Or three.

Okay, knowing you’ve been warned…

I never played ball with Dad. Or actually, Dad never played ball with me.

In my youth and growing up through high school then into college, I was fortunate to have good success as a baseball, soccer, and football player. Growing up I was Steve Garvey, first baseman for the LA Dodgers; Shep Messing, goalie for the NY Cosmos; and Earl Campbell, running back for the Houston Oilers. And then on the concrete or gravel where Dad put up a hoop, I was also Larry Bird of the Celtics though I never played organized team basketball (that was Clary’s game!). Throughout my entire, though brief, athletic career that ended my junior year in college when I played a final year of football at CWU, there isn’t a single time when I remember Dad doing any kind of coaching or teaching or anything that resembled practice to help me get better at any of the sports I played. We never played catch, he never pitched batting practice to me, he never hiked or threw a football to me, he never showed me how to tackle or stiff arm someone, he never tried to score against me with me in net. I have vague memories when he would join us briefly to shoot some hoop but never a game of 21 let alone HORSE (well, maybe a game or two of PIG). And I also have a couple of tender and sentimental memories of Dad, late at night, under the floodlight of the garage that lit up the area where the hoop was placed, shooting baskets all by himself (I SO wish I could go back in time to ask him what he was thinking about in those solitary moments—‘cuz it wasn’t about becoming a better basketball player…of that I can assure you!).

Dad never really brought us to any of our practices—keep in mind growing up on the farm, every one of the sports I was involved in took place during “hop season.” Hop season went from late winter of the previous year to early winter of the next so getting a farmer away from his farm was a difficult thing to expect; especially when there was a mom in the house who had her own car, had the time, and I guess the interest. It’s only mom that I can remember on the sidelines of most of our practices and much of our games. Playing little league in Toppenish, I remember mom would always bring us to our games and I have a recollection of Dad’s pickup driving up mid-game but Dad not really getting out of the truck at all. And the truck was gone by the end of the game—there was likely irrigation that had to be checked or changed back on the farm before sundown.

Growing up and into more of our sports interests, there was a growing tension between mom and Dad about this—with mom at times showing her frustration at Dad for not being more present or showing more interest in our athletic endeavors. Mom got good at the whole “Catholic guilt” thing. It changed a little when Trevor and I got into high school and the stakes of our games in our little town of Moxee, where Friday Night Lights were kind of the biggest thing to happen in that small, tight-knit community—even during East Valley’s 40 plus game losing streak that ended the second football game of my junior year. THAT was a big deal! We saw Dad at every football game of ours during high school—and the games in the early part of the season took place during hop harvest (so, yeah, it WAS a big deal).

But here’s the thing—and I think I do speak for Clary and Trevor on this point: whereas you might think Dad’s inattention or “lack of interest” was a negative influence in our lives such that we harbor resentment for his “not showing up,” you would be mistaken. Not once did I ever, EVER, feel like Dad was abandoning his boys when they left the house to go to their sports. And it’s weird because we had ample ammunition that could have fed that feeling. Mom always had us covered by insuring we stayed on schedule; but Dad…Dad we knew, intuitively, something different was at play.

I’m even going to go a bit further—Dad never showed any interest in our schooling either. I cannot recall him ever asking anything about any of the classes I took, any of the experiences I had in school, or any questions about my homework. Consequently, I never asked him to help me solve geometry problems or how to conjugate certain verbs in essays I wrote. He never inquired about girlfriends (there weren’t a whole lot anyway). And he never knew what my favorite subjects were, nor why, during any of my 17 years of schooling (K through college). And I’m still waiting for the “birds and bees” conversation (although I do believe I figured certain things out!)

I can’t recall Dad ever saying “That was a great game Kert!” Or “One heckuva home-run today!” Or “Another shutout, eh? Well done son, very well done!” Or even “Nice work acing that trig exam!” He never “told” me he was proud of me. That kind of praise, along with any skill at coaching any sport, didn’t come easy to Dad. So he never really had a go of it. He left that all up to mom and was content in doing so, not that he had much of a choice anyway—mom was very happy to be the focal point of all that glam and attention; Catholic guilt-tripping notwithstanding.

Dad wasn’t an absent dad even though he wasn’t always present. Weird, huh? We knew where Dad was—working his ass off on the farm and doing THAT virtually all by himself. We saw him, every day, on our way to school already out in the fields, discing, or training, or plowing, or burning weeds, or setting irrigation. And when we got home, we saw him out in the fields, discing, or training, or plowing, or burning weeds, or setting irrigation. Day after day after week after month.

No, Dad wasn’t an absent dad. We knew where he was. And it was only later that we realized what he was teaching us during all that time.

We knew his love for us was absolute and unconditional. And I knew something else too that wasn’t confirmed for me until the middle of my senior year in high school.

You see, I was fortunate enough to enjoy a level of success, thanks completely to my coaches and teammates, that brought a few awards and recognitions my way. One of those recognitions involved an awards banquet ceremony at which I was expected to speak to an audience for an acceptance speech. We sat in a place “of honor” at the head table in front of, maybe, 300 business people in Yakima for the recognition luncheon—another big deal as this happened in the middle of a school day and a day out in the fields. As I began, mom and Dad were situated behind me so I couldn’t see them. But I heard Dad. Dad was, for the first time I had ever heard in my life, sobbing out loud out of a sense of pride. For a second, I didn’t understand what I was hearing and I almost stopped speaking to turn to my Dad. But then I realized what was happening. And I kept on going.

My Dad was so very proud of his son. And his son was hearing about that pride, in such an unexpectedly authentic way, for the very first time in his life. I’ve never forgotten that singular moment. That was an eldering lesson for me; one that I’ll never forget.

I heard it a couple more times over the rest of my athlete career. And now, especially after mom died in 2016, we all hear it often—his pride and love manifested in a choked-up “I love you, I miss you, goodbye” salutation that happens virtually every time there is a conversation, even one over the phone. We know THAT is his way of showing his love, and his pride. Ironically, mom’s death gave us that more emotionally raw and available Dad. Now, words do have deep meaning for Dad—because those words are woven into a tapestry with the deep emotions of love, longing, and gratitude.

Maybe that’s why mom had to die first. So that we could experience our Dad for reals. He was always a man of heart, even when he hid it from us growing up. He can’t hide it from us anymore.

Some cinematic asides:

In the comment section of one of the YouTube clips, a person wrote: “There are two types of men in this world, those who cry at the end of Field of Dreams and those who lie about crying at the end of Field of Dreams.”

I’m not gonna lie: I cry at the end of Field of Dreams…Each. And. Every. Single. Time.

Heck, even the soundtrack by itself gets me…Each. And. Every. Single. Time.

Fun fact but another spoiler alert—so I recommend watching the clip, or watching the entire movie again, before reading this: When the filming of the movie wrapped, and the director was in the final editing process, something had been nagging at Kevin Costner about the ending. He felt it didn’t have the emotional “punch” that was called for at the end of this iconic quest. This was also confirmed by some audience screenings that were done prior to the theatrical release. Audiences hated that the two characters didn’t, in some way, recognize their relationship (even though Ray comes close when he introduces John to Karen, his granddaughter). Costner then hit upon an idea and therefore convinced director Phil Robinson to allow him to dub over one line in post production, a change of only one word actually, that was different from the script and from what was actually filmed—and it is THAT line, the change from the intended word to the word we hear in the film, I think, (at least it’s true for me), that ALWAYS brings tears because it touches a very tender and dear spot in the hearts of most sons—whether or not they’ve ever played baseball. And you can hear it catch in both Costner’s voice AND Brown’s (the actor who played John). ‘Cuz in THAT moment, we learn the movie was not about baseball. The entire movie is about fathers and sons.

The line?

“Hey dad? Want to have a catch?”

The line from the script as spoken by Ray initially in the movie was: “Hey John, want to have a catch?” You can tell Costner’s voice was dubbed into that spot because in the movie, as you can see in this clip, the camera isn’t on Costner when he says it. The camera stays on John, dad, as he walks away.

That one line was worth the price of admission—1000 times over.

Dad and I never “had a catch.” And I’ve NEVER, ever held it against him. Not one single moment. Instead, he gave me something different, something more meaningful now, something with greater depth. Dad gave me, through his example, the meaning of what a single-minded pursuit of excellence and perfection could produce; how, through incredible devotion to something larger than any one person, without any need for acclaim or praise, and through extraordinarily hard work and absolute humility and kindness, how a life so dedicated could create for oneself a life of meaning, integrity, and authenticity.

And how such a life, such a man, could produce a family he was so tremendously proud of. And a family who knew it even if they didn’t hear it from him. Dad’s life taught us that actions speak louder than words.

I’ve never needed anything more from him. Not even a catch.

All THIS has been one way I know Dad as a dad. And this is why he is here with us now.

Maybe we’ve built for him here in Lake Stevens his “Field of Dreams;” maybe we’ve built it for us too. And if so, then, not so metaphorically…

…it’s not Iowa, but maybe this IS heaven—a place where dreams come true.

T plus ___ …and counting. It’s important now, as we walk with Dad in his “bottom of the ninth,” that we recognize each day as it truly is—significant. That’s what knowing death is coming can do: it can remind that soon there will be only one day left. That’s death’s value—its gift to us. Every single day is significant—like every “at bat” in a world series.

We just have to realize there are NO other days—only THIS day. Always and ever. THIS is the only day we have.

Which, ironically, ties things to…

*** that other 1989 movie?

“Dead Poet’s Society.” This movie inspired me so much that I created and taught an elective class on poetry to some of my junior high students.

“Seize the day, kids. Seize the day. Make your lives extraordinary!”

Very well said! Dad was a behind the scenes Dad with not much input on our athletic endeavors! But, if anything was evident it was his pride in his children!

I miss Him more and more every day! I miss His glee at beating me in horseshoes or cards! He was defiantly a unique person, and I loved Him for that!

My Dad and I never “ had a catch” either.