This week, I’m doing something I haven’t ever done—at least by way of writing and posting about it. I’m not a book critic, and the only English courses I took in college were the ones required for my undergraduate degree. I had NO inkling to minor, let alone major, in English. And truth be told, I’m still not sure I read books, especially books of fiction, like I should. Sometimes I miss the hidden messages that surface an author’s original intent. Sometimes I miss the allegory, the metaphor, of how the story as written is actually a way to interpret the deeper aspects of life. Sometimes the story is just the story to me.

I was never taught that I really didn’t have to discover the author’s true intent but that I could make those connections myself. I was never taught that I could enter into a story asking what that story might have to teach me about myself. It’s been only due to my lifelong reading habit that I’ve evolved my reading to appreciate this deeper level of reading. This time lag might actually be due to the fact my preferred genre is non-fiction—a genre that, by definition, excludes hidden metaphors, meanings, and messages.

But this week, as I said, I intentionally did something I typically do not do.

I think we are in the midst of a great, dark, and noisy storm—a storm that has already swept up the politics, culture, and society that was the United States of America. And now we are watching as that storm is quickly moving across the entire geopolitical landscape that is planet Earth—at least those ‘scapes inhabited by humans.

By all accounts and observed evidence, we are in the midst of a major tempest.

Tempest (noun)

literary. a violent wind or storm. a violent commotion, uproar, or disturbance.

(Dictionary.com 2025)

Key word: VIOLENT

So, I did something different this week. Have I mentioned that already?

When faced with going through the doom of an impending tempest, one cannot avoid it, hide from it, pretend it’s not happening, or even fight against it in habitual ways. What one CAN do is look for guides who’ve gone through similar storms. So, I did that this week. And I picked a pretty good guide.

I picked William Shakespeare.

Ships in storms essentially become rudderless—and I’ve often felt rudderless these past few months. I feel as if our country is still rudderless. But I also know that remaining rudderless is sometimes a choice, too. And I can choose something different.

Enter Shakespeare.

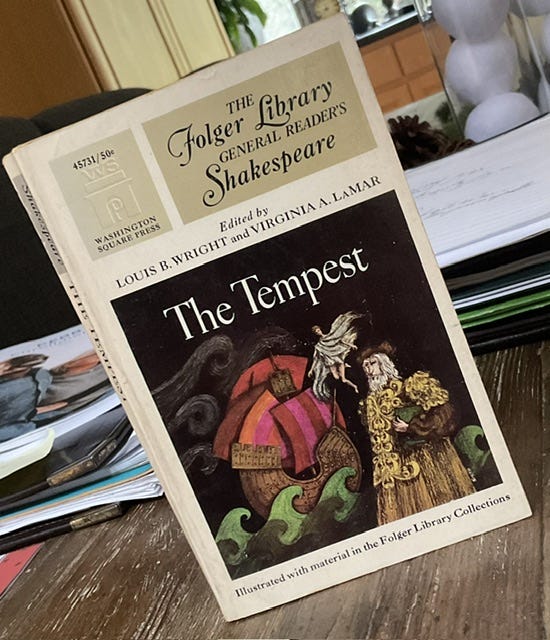

I used to read Shakespeare often—usually a couple of his plays a year in addition to a lot of his poetry. But I realized it had been a while. So this past Monday, I dusted off my Folger Library trade paperback copy of The Tempest and settled in. Now, I just as easily could have chosen King Lear, Macbeth, Othello, or Julius Caesar (maybe especially Julius Caesar—you know, he of the “Ides of March” and “Et too, Brute?” fame?), as apropos guidebooks. And maybe I’ll do this same kind of reading with some or each of those soon. For certain, the times call for dipping into any of Shakespeare’s tragedies—not the comedies.

Interestingly enough, despite the title, The Tempest is classified as a romantic tragic/comedy.

Although The Tempest is listed in the First Folio as the first of Shakespeare's comedies, it deals with both tragic and comic themes, and modern criticism has created a category of romance for this and others of Shakespeare's late plays. The Tempest has been put to varied interpretations, from those who see it as a fable of art and creation, with Prospero representing Shakespeare, and Prospero's renunciation of magic signaling Shakespeare's farewell to the stage, to interpretations that consider it an allegory of Europeans colonizing foreign lands.

~ Wikipedia, 2025

We aren’t right now living in comedic times—even as defined Shakespearially. (But, god willing, maybe at some time years hence, we shall look back upon these times as America’s greatest comedy, Shakespearially speaking. God willing, please.)

Side note for reference:

The Tempest is “the one” with the following famous characters and quotes:

Prospero, Caliban, Miranda, Ferdinand and Ariel.

“Full fathom five thy father lies.” (Ariel)

“Keep a good tongue in your head.” (Stephano)

“What’s past is prologue.” (Antonio)

“Misery acquaints a man with strange bedfellows.” (Trinculo)

“We are such stuff / As dreams are made on, and our little life / Is rounded with a sleep.” (Prospero)

“How many godly creatures are there here! / How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world / That has made such people in it.” (Miranda)

Silly Miranda. Anyway…

Shakespeare set the opening scene of The Tempest on a ship at sea amidst a brewing storm with chaos ensuing; and then afterward, an uninhabited island where nothing looks familiar and everyone is discombobulated, confused, forlorn, and divided. Sound familiar?

Metaphors, metaphors, metaphors.

I didn’t just pick up the play to reread it cold. I did something different: I asked something of it. I asked Shakespeare himself a question. This question:

“Do you, William, have something to say to us, today, in our own times, as we attempt sail through this horrendous tempest?”

He had an answer, sort of.

William’s “sort of” caution:

The Tempest is a play with grand themes of magic, betrayal, love, retribution, vengeance, banishment, servitude, power, title, royalty, transactional loyalty, indebtedness, entitlement, and then ultimately accountability, forgiveness and reconciliation. If you note some of those themes, they match starkly with some of the themes we are seeing play out in our politics right now. But because Shakespeare wrote it as a romantic comedy, he ends it with an all too clean way of resolving all conflict through acts of absolution, reconciliation, and forgiveness.

Prospero, the play’s protagonist, had vengeance in his heart to begin the action; so using magic, he caused chaos to ensue that served to divide a people, wreck their ship (of state?), cause harm and strife, spread abject lies, and test loyalties. Sounds pretty metaphorical. Prospero initially seeks retribution for having been forcefully dethroned and banished to a deserted, uninhabited island (hmm…loss following first term, banished to a gaudy Florida golf resort clubhouse, the need for retribution… anyone? anyone? Bueller???).

While on the island, Prospero sees a way, and takes full advantage of it, to achieve vengeance and settle scores through lies, deceptions, gaudy pageantry, cunning planning, the forming of coalitions and tribes, dark magic, and sleazy information gathering. There are even loyal sycophantic servants who attempt to do Prospero’s bidding by staying in his good graces. They’ll do anything to curry favor with Prospero while at the same time loathing him and counting the days when even he will be dead—some even planning, and almost carrying out, his assassination. Even a beloved daughter questions her father’s sanity and intentions.

All that, metaphorically speaking, sure does sound spot on familiar, right?

And then Bill (sometimes I call him Bill), writes Act V.

Act V

The final act is a rather speedy resolution of the play’s conflict with all characters. This is where the play’s metaphor, if I were seeking a parallel to the politics of today, breaks down completely. I wanted something different—this made me wonder just how far back it was when I first read The Tempest; or if I indeed had even read it before. Because, I thought a different teaching was within the work.

But like all great literature, the author throws curveballs until you finally get it.

In Prospero, Shakeseare has created a man, a wizard and dethrowned royalty, with a moral conscience, though we don’t see it until the very end, in the final epilogue spoken by Prospero himself. The way the play’s action gets resolved is through this man’s compassion—his abnegation and renunciation of his influence, even of his magic, and to ask forgiveness of the audience. He has realized that he is not “all-powerful” despite his magical powers, and that revenge and retribution solve absolutely nothing. Ultimately, he must move to a higher realm of consciousness—a realm that has mercy, justice, and forgiveness as its foundation.

“…my ending is despair / Unless I be relieved by prayer, / Which pierces so that it assaults / Mercy itself and frees all faults. / As you from crimes would pardoned be, / Let your indulgence set me free.”

~ Prospero

In the end, Prospero sets his captives free, forgiven of all transgressions, and insures their journey back to their homeland will be safe. It’s a happy ending.

But THAT’s not a’happening here, in present day 2025. At the highest rungs of our political leadership, there is nary a single moral conscience to be found. And both vengeance and retribution continues to ensue chaotically. By definition, there are no happy endings in tragedies.

So maybe, in Prospero, Shakespeare is reminding us that if we choose our leaders well, and we MUST!, even when they fail to meet our sometimes too lofty standards of hope and excellence, when they disappoint us, we can still count on their basic moral goodness to know where the boundaries of civility, humility, and common decency are drawn—without stepping over them. That in the end, they will do right and treat others with compassion.

Maybe someday in elections hence, we’ll get back to electing people like that.

Maybe.

Always and Ubuntu,

~ k

Postscript:

I think to gain a better sense of the tragic nature of our current reality, and to trust better that Bill Shakespeare really did have something important to say about the nature of power and greed: ie that “power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely”, I do need to read a different play. The Tempest ends on too moral a high and happy note. And there is nothing about today that has proven to have any basis in moral or ethical correctness. Let alone happiness.

Interestingly though, and I kid you not, Shakespeare writes this line in Act IV. SC. 1:

“The trumpery in my house, go bring it hither / for stale to catch these thieves.”

Trumpery = trifles; stale = bait.

Fascinating. Just…fascinating.

I need to reread one of Shakespeare’s darker tragedies. It fits both my mood and our times better. And I think I know the one to read because years ago, I read it and remember having a reaction to it because of its brutality. I agree with what Shakespeare had his Antonio say here in The Tempest, that “What’s past is prologue.” The world has had leaders such as this over the course of its human history. And yet, despite their single-mindedness in the pursuit of absolute power, and the intentional harm created in their wake, they still rise to power because the populace, who could have, do not stop them—especially in so-called democracies.

William Shakespeare, I fear, wrote about today when he penned The Tragedy of Richard III.

I shall see.

What an excellent task for yourself to look to ole Bill to help give some perspective on the shit storm being played out.

Stepping out from home,

from our haven in the storm.

Bringing lanterns, love?