Are you like me and always prefer the book to the movie? I’m not sure I’ve ever seen the movie adaptation of a book be better than the book itself. Sure, some come close—Harry Potter, To Kill a Mockingbird, The Godfather, The Lord of the Rings. But, naw, the books are always better.

Except when they’re not.

This particular book was a natural for me to pick up. I was a science geek and teacher keen on anthropology, Darwinian evolution, archeology, and paleontology—the study of fossils. The book’s main character, well, the one with two legs anyway, was fashioned after perhaps the most famous dinosaur fossil expert in the world: Dr. Jack Horner. This guy ⬇️

This guy, Dr. Horner, in addition to his day job, served as the technical advisor, as he should have, to the first five movies in the franchise that was kicked off by the book I’m starting to describe to you.

Do you know the book I’m speaking of?

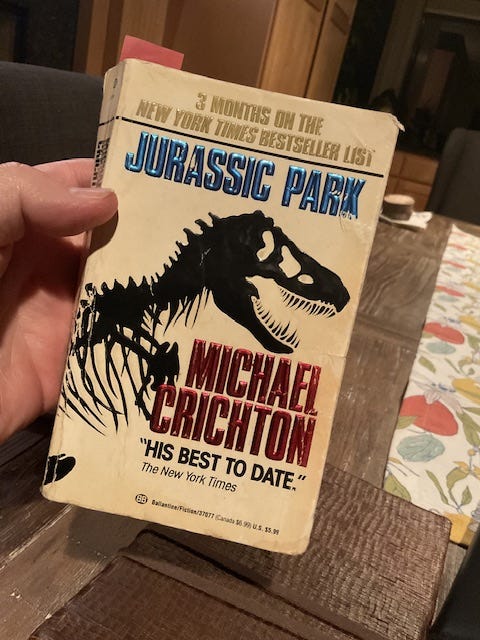

It was written by this man: ⬇️

This is the same man who created the TV medical series E.R. The same man who wrote 20 books BEFORE the book I’m talking about.

Okay, I’m being a little coy. Sorry.

What this post is REALLY about

Micheal Crichton, that second guy above, was an incredibly talented (genius actually) and prolific individual. He died much too young, at the age of 66, in 2008. The first book I read of Crichton’s was the 20th book of his that was published, in 1990. It was made into a movie in 1993–remarkably soon after the book’s publication—the book was THAT popular. Steven Spielberg, the movie’s director, said that the movie couldn’t have been made at any time sooner because there was no way to insure the movie itself was faithful to, and honored, the story of the book—and all its characters. Not the human characters mind you, the dinosaur characters—T-Rex, the “veggiesaurus” (see what I did there? Achoo!), the triceratops, and the velociraptors.

The book is amazing—one of my all time favorites. I remember sitting in the theater when the movie came out and it, too, blew my mind! I remember thinking as I was walking out of the theater: “Now THAT’s how you adapt a book into a movie!”

But here’s the funny thing: just the other day, in a quiet moment I had staring out at the trees past our back yard, I realized this book I loved dearly, and actually taught from when I was a science teacher, was not a work of science fiction; nor was it a work about dinosaurs—or even dinosaurs brought back to life. The book is a metaphor—and this was Crichton’s genius. Even though the science behind the book is rock solid and no longer just theoretically possible, Crichton wasn’t writing about one billionaire’s quest to create an island theme park where the main attractions were live dinosaurs brought back from extinction through the extraction of their DNA found in the guts of insects that were trapped in amber; nor all the events that occurred when that billionaire brought the quasi Dr. Jack Horner (aka Dr. Alan Grant), his female assistant, a couple of kids, and a quirky mathematician/chaos theoretician, to the park on a trial tour. He wasn’t writing about any of that at all. But up until recently, I had the metaphor wrong.

See, I imagined at one time the metaphor of Jurassic Park was an historical lesson on the making of the first atomic bomb. Each character in the book an avatar of a real person or thing (I’ll not bore you with whom I think these relate—if you are interested, and know both the book and your WWII history, or have seen the recent Oscar winning movie “Oppenheimer”, have a go at it yourself). Remember, though, I had the metaphor wrong. I pegged Crichton as an historian—he was, instead, an oracle—the book a prescient tome on the unimaginable dangers of a technology that would take 30 years to develop past the date of publication. The T-Rex of Jurassic Park wasn’t a T-Rex, nor was it either “Fat Man” or “Little Boy,” (the names given by the scientists of the first two atomic bombs created in New Mexico in the 1940’s).

No.

Crichton’s T-Rex is better known to us by two letters. Two letters that form an abbreviation of a two word, 22 letter designation of something that has no form or body, that cannot be held, cannot be touched, has no heartbeat, has no emotions—for that matter has no senses whatsoever—and just might have unlimited power that exceed’s the human capacity to tame it. It is, already, fundamentally changing our world. And because I’ve linked the T-Rex to it, perhaps you can tell, now, how I feel about … A.I.

Artificial Intelligence.

Here is Crichton’s first paragraph of Jurassic Park:

“The late twentieth century has witnessed a scientific gold rush of astonishing proportions: the headlong and furious haste to commercialize genetic engineering. This enterprise has proceeded so rapidly—with so little outside commentary—that its dimension and implications are hardly understood at all.”

Like its comparison to the making of the bomb, the metaphor applied to A.I. also has its character avatars/analogues. Like the T-Rex, which is simultaneously THE fiercest danger and predator in Jurassic Park, the one Dr. Alan Grant was most scared of, and the one who served, ironically, as a quasi-hero at the end, Artificial Intelligence has been heralded as both THE pinnacle of scientific advancement, such that everything from here on out will be touched in some way by it; and the most dangerous “thing” that humans have ever produced—so dangerous, like the quote above from Crichton’s first paragraph, no one, NO ONE fully understands its dimensions and implications. In the hands of bad actors, the atomic bombs, heck, even the hydrogen bombs, are mere firecrackers to the devastation that A.I. could (will) unleash upon the world.

It was literally just months ago when even the very computer scientists who perfected A.I. models were saying “we need to maybe slow down or stop development until the government can put some regulations on this. Hell, we don’t even know what could happen with this.”

Funny that.

Fun fact: In laboratories all over the world, geneticists (and likely billionaires) ARE actively in pursuit of bringing back species that have gone extinct. And they are getting closer, and closer, and … closer. Last month, news came from a private research lab in Dallas of mice successfully bred with Woolly Mammoth genetic traits.

The ultimate GMO—Genetically Modified Organism, if you will. Until, that is, they turn their attention to Tyrannosaurus rex.

My favorite quote in Jurassic Park was said by Dr. Ian Malcolm, the quirky mathematician played brilliantly by the brilliant Jeff Goldblum:

"Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn't stop to think if they should."

~ Dr. Ian Malcolm (aka Jeff Goldblum aka Michael Crichton)

A.I. has the power to do much good in the world—spoiler alert I: it already is, especially in the health sciences. But, I don’t believe, at all, that it’s our friend. Because I know human nature, and I know the almost infinite capacity humans have to destroy things, including each other, A.I. WILL be used for dangerous and nefarious things (spoiler alert II: it already has!). Some will try to argue that the benefits will far outweigh the dangers. But I don’t think so. A.I. is every T-Rex and velociraptor rolled up into a string of 1’s and 0’s in the imaginary, binary “cloud” that, at the push of few buttons of input, from the wrong people (who are alive today and planning just this), will make Hiroshima and Nagasaki look like a bad day at Disneyland—let alone a jeep tour gone wrong during a storm at Jurassic Park.

Near the end of the book, Dr. Malcolm and the billionaire John Hammond (played equally brilliantly by Sir Richard Attenborough), engage in a thoughtful discussion that serves as the book’s penultimate crescendo—but also its moral lesson. At the end of the discussion, Crichton has Malcolm say this:

“Let’s be clear. The planet is not in jeopardy. WE are in jeopardy. We haven’t got the power to destroy the planet—or to save it. But we might have the power to save ourselves.”

Humans are silly when it comes to dreams like that—the dreams we continue to have that we will be able to stay in control of the technologies we create. We continue to build systems and weapons and technologies and ideologies and cult-like followings that have us “thisfreakingclose” to a human-created, human extinction event. Up until now, a human has always stood in the way of the final button being pushed. This time, however, something has been created that can, and likely will, push the button without human interference. And maybe even without human agency.

An ironic aside: a decade before the Jurassic Park movie, in 1983, there was a different movie that imagined this exact scenario! Do you recall it? It, too, is an excellent movie—less a metaphor, more a prescient fictional “documentary.” I’m not sure it was adapted from a book—if it was, I didn’t read it. In War Games, staring Matthew Broderick, Joshua (aka W.O.P.R.: “War Operation Plan Response) is the spot-on stand in for A.I.

“A strange game. The only way to win, is not to play. How about a nice game of chess?” ~ Joshua’s final words.

Like with anything new, we should, but have lost the capacity to, ask critical questions: Who benefits? What are the costs (for there are always costs)? What is the best that could happen with this? What is the worst that could happen with this? Who will get hurt and how? Who controls access? Is there an ‘off’ button? Who’s in control of that button? Who’s ahead of ‘us’ in development? (And who is ‘us’ anyway?) What protections and/or guardrails need to be in place? Can those be held sacred by everyone? How will we know?

Just because we can, should we? And…

Why?

Near the end of the novel, Ian Malcolm says this:

“And now chaos theory proves that unpredictability is built into our daily lives. It is as mundane as the rainstorm we cannot predict. And so the grand vision of science, hundreds of years old—the dream of total control—has died, in our century. And with it much of the justification, the rationale for science to do what it does. And for us to listen to it. Science has always said that it may not know everything now but it will know, eventually. But now we see that isn’t true. It is an idle boast. As foolish, and as misguided, as the child who jumps off a building because he thinks he can fly.

“We are witnessing the end of the scientific era. Science, like other outmoded systems, is destroying itself. As it gains in power, it proves itself incapable of handling the power. Because things are going very fast now. Fifty years ago, everyone was gaga over the atomic bomb. That was power. No one could imagine anything more. Yet, a bare decade after the bomb, we began to have genetic power. And genetic power is far more potent than atomic power. And it will be in everyone’s hands. It will be in kits for backyard gardeners. Experiments for schoolchildren. Cheap labs for terrorists and dictators. And that will force everyone to ask the same question—What should I do with my power?—which is the very question science says it cannot answer.”

“So what will happen?” Ellie asked.

Malcolm shrugged. “A change.”

“What kind of change?”

“All major changes are like a death,” he said. “You can’t see to the other side until you are there.”

Malcolm sighed. “Do you have any idea,” he said, “how unlikely it is that you, or any of us, will get off this island alive?”

(Sigh).

Boys and girls…

Sleep well.

Always and Ubuntu,

~ k

Great, love this quote

@Let’s be clear. The planet is not in jeopardy. WE are in jeopardy. We haven’t got the power to destroy the planet—or to save it. But we might have the power to save ourselves.”

"Who benefits? What are the costs (for there are always costs)? What is the best that could happen with this? What is the worst that could happen with this? Who will get hurt and how? Who controls access? Is there an ‘off’ button? Who’s in control of that button? Who’s ahead of ‘us’ in development? (And who is ‘us’ anyway?) What protections and/or guardrails need to be in place? Can those be held sacred by everyone? How will we know?" AND who has the answers to these questions?

Here is an ancient folk tale for our time.

High in the Himalayan mountains lived a wise old man.

A few young boys from the village decided to play a joke on the wise old man and discredit his special abilities.

The boys devised a plan.

They would catch a bird and ask the old man if the bird was dead or alive. If the wise man said the bird was alive, the boy would crush the bird in his hands, so that when he opened his hands the bird would be dead; if the wise man said the bird was dead, the boy would open his hands and let the bird fly free. So no matter what the old man said, the boys would prove the old man a fraud.

The boys walked up to the wise old man and asked, " Old man, old man, tell us, is the bird alive or is it dead?"

The wise old man looked at the boys and said, "The answer is in your hands, as you choose it to be.”