Dying Wiser #12: An Apprenticeship With Sorrow

Wisdom Through Literature; Eldering Through Dad: Having Faith In Grief

The other day, in an unexpected moment, I paused as Dad and I were leaving the toilet area and I really looked at him, perhaps more deeply than I ever have…and I became sad. That was unexpected too. Something like that hasn’t happened very often, a sadness felt to that degree; maybe the winter season is going to provide more fertile soil for that to happen more often as I’ve had difficulty in weathering the winter months in my past. I’ve always attributed that to “SAD-lite: Seasonal Affective Disorder without a diagnosis.” But ironically, it suits well my melancholic tendencies anyway. I’ve never minded the grey; never minded the rain nor the cold; nor sadness even. In that space, soul resides. I find it comfortable—and comforting.

I know Dad is no where near the man he was when he was a vibrant and virile farmer, tending his over 250 acres of farmland and machinery. We are well into his third decade of retirement after all. And you all know, if you’ve been a faithful reader of these posts, that his decline started the day he let it all (the farm that is) go. But things are “more different” now. Dad is physically a much smaller man. I tower over him especially since he is no longer able to stand fully upright—so when I looked in depth at him the other day, I was looking down. For a lot of my life, I had always looked up at him even as I surpassed his 5’8” frame (I do still look up to my Dad in the ways that matter most though). He is frail—and becoming more so. The skin on the backs of his hands and his arms is too prone and too easy to tear now—the loss of elasticity. He is losing strength—as in the “he can’t even push himself backward in his recliner to lift the footrest nor can he pull himself forward to lower it” loss of strength; combined, maybe, with the degenerating neurological/muscular coordination to do so. We don’t eat upstairs anymore—those stairs are too much the obstacle and danger now—so we eat downstairs as a family. With Sammy doing vacuum duties still.

And inside, inside himself, he’s becoming a stranger even TO himself as he continues the loss of who he was. Is it strange for me to say I know he’s my Dad, but I don’t know who this man is? He’s becoming a stranger even to me as I am realizing now: I’m losing the familiarity of my father.

I am losing my Dad.

Fucking dementia!

(And this time, I respectfully do not ask for your pardon because I trust you agree—dementia really sucks!)

“Where there is sorrow, there is holy ground.” ~ Oscar Wilde

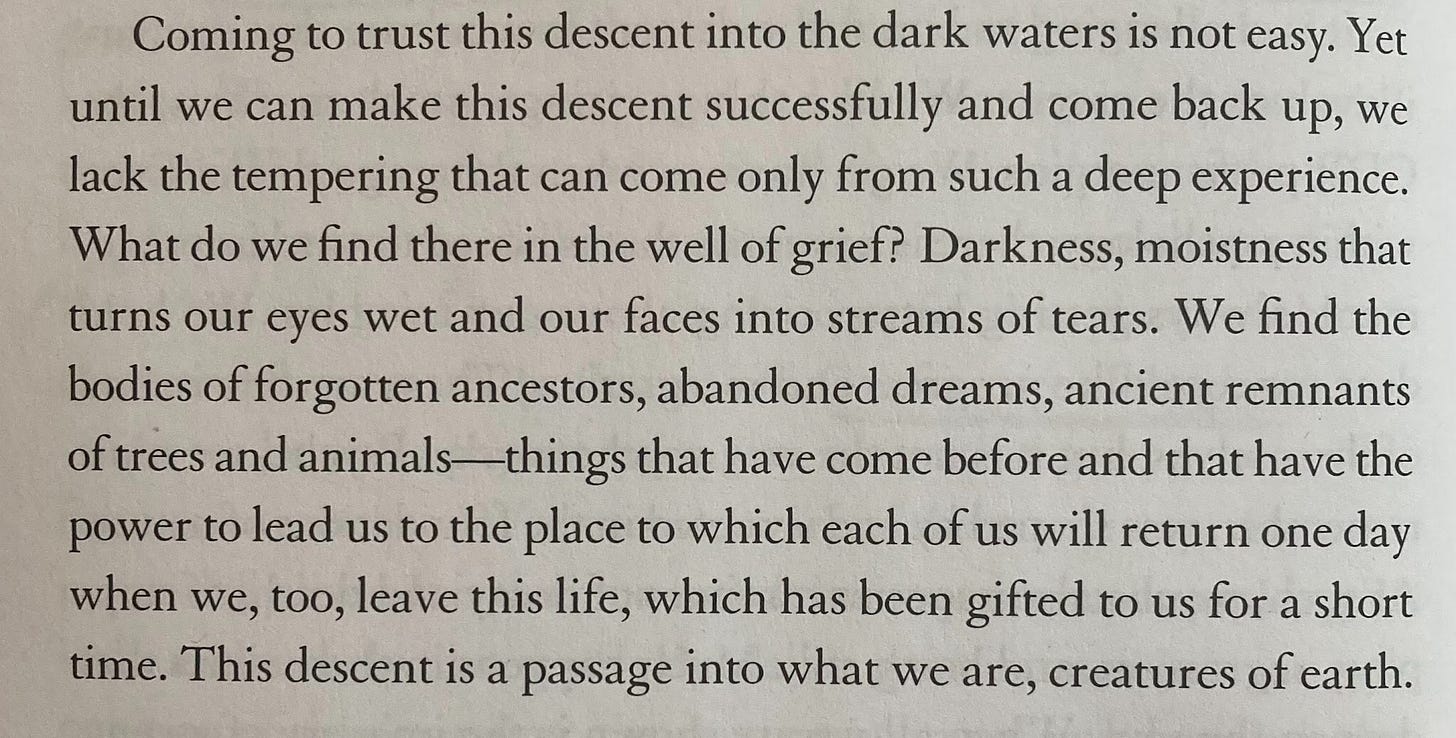

And so we walk, now, into the beginning space and time of grief in earnest. Should we choose to do so, that is. And we should. We don’t HAVE to inhabit the liminal, dark, organic and fertile landscape that is grief, but we ignore it at our own peril. There is a great cost to believing grief isn’t a thing—that death and sadness can be locked away in the nether regions of hearts to lessen our pain. Such folly that. “Going there,” leaning into that dark place, is a choice. And turns out it is the healthier choice. It is better to approach this time with Dad with an open and full, if even an “about to be broken,” heart. To approach him and this time with reverence.

And I am trying.

Each day a next step deeper into the mystery that is sorrow, that is grief. There is no going back—only onwards and through.

“Grief is a form of loving that which has passed from view. Love is form of grieving that which has not yet done so.” ~ Stephen Jenkinson

< 2

In last week’s post, I shared we had a 1 + 1 < 2 moment during Thanksgiving.

Here’s another moment to call out the fact this next sharing, this next update on Dad’s wellness that I’m about to provide, isn’t meant to sensationalize the dramatics involving Dad nor to compromise his dignity nor to breach confidentiality. The intention is to always maintain his dignity—while at the same time honoring his lived life as an Elder for us all. And remember, Elders ALWAYS lean into darkness—that is where Elders are needed the most.

At a family Thanksgiving meal, at the dinner table itself and as we were finishing eating, Dad had a convulsive seizure.

He’s never had a seizure before in his life—to our collective knowledge. Now, if you are going to have a seizure, I do recommend that you do it like Dad did: have, sitting mere feet from you, both a registered nurse (Cassidy), and a veteran first-responder, professional fire fighter (Trevor). Having a former principal there is optional. In that “less than two” scary moment, we could not have been better able to respond.

I was sitting directly across from him on the other side of the table—if I’m not directly at his elbow, I’m in a place at least where I can see him fully. He was finished with dessert and we were about ready to start cleaning up the dishes when Dad grew teary. I thought he was about to say something to his family which, nowadays, always comes with tears. I think I remember asking him “Dad, it looks like you want to say something.” The room quieted and all eyes turned to Dad, which was also the exact moment when, as he was starting to speak, he had a NES (“non-epileptic seizure”). His body convulsed…and he began to slump over. Trevor caught him as he was falling to the floor—and Cassidy was right there on the other side of Dad to support him. Though Dad never lost consciousness, he did scare the heck out of us.

Things are more real now than they have ever been.

And so, the Approach with Reverence…

At the start of every month, I have a ritual that has come to be something much more meaningful since Dad has joined us. The ritual involves three special books written by authors I consider among my most powerful Elders and teachers. On this recent first of December, whereas I usually read special selections from each book, I was drawn to only one. I’ve read this book about a half-dozen times now in it’s entirety; and it is constantly at my elbow during times of sacred moments. I am currently re-reading the entire book yet again because it, and these times, are calling me to do so. Today’s wisdom literature comes from that book: The Wild Edge of Sorrow: Rituals of Renewal and the Sacred Work of Grief by Francis Weller.

First, two definitions:

grief (n)

a deep and poignant distress caused by, or as if by, bereavement; feelings of deep and heavy sadness associated with loss.

(Merriam-Webster, 2022)

“The territory of grief is heavy. Even the word carries weight. Grief comes from the Latin word gravis, meaning “heavy,” from which we also get grave, gravity, and gravid. We use the word gravitas to speak of a quality in some people who are able to carry the weight of the world with a dignified bearing. And so it is when we learn to carry our grief with dignity.” (Weller p. 15)

reverence (n)

rev·er·ence ˈrev-rən(t)s

1: honor or respect felt or shown : DEFERENCE especially : profound adoring awed respect

2: a gesture of respect (such as a bow)

3: the state of being revered

(Merriam-Webster, 2022)

Weller, who is a soul-centered psychotherapist and self-described “soul activist,” is also a fan and devotee of the late poet John O’Donohue. In his book he quotes from O’Donohue a passage that I, myself, began using a couple of years ago when I evolved my principalship toward its own advocacy of soul—especially the souls of the kids and staff I served. Here’s the lovely quote from O’Donohue:

What you encounter, recognize or discover depends to a large degree on the quality of your approach. Many of the ancient cultures practiced careful rituals of approach. An encounter of depth and spirit was preceded by careful preparation. When we approach with reverence, great things decide to approach us. Our real life comes to the surface and its light awakens the concealed beauty in things. When we walk on the earth with reverence, beauty will decide to trust us. The rushed heart and arrogant mind lack the gentleness and patience to enter that embrace. —John O’Donahue, Beauty: The Invisible Embrace.

(in Weller p. 4 and also www.johnodonohue.com/reverent-approach)

Weller continues the thought:

“How we approach our sorrows profoundly affects what comes to us in return. We often hold grief at a distance, hoping to avoid our entanglement with this challenging emotion. This leads to feeling detached, disconnected, and cold. At other times, there is no space between us and the grief we are feeling. We are then swept up in the tidal surge of sorrow and often feel as though we are drowning. An approach of reverence offers us the chance to learn a more skillful pattern of relating to grief.” (p. 4)

The times in which there is “no space between us and the grief we are feeling” when it comes to my father are increasing—in both frequency and duration. Dad, for me now, is the full embodiment of grief, and source of grief—of a time of capacity that no longer exists, of strengths and abilities abandoned to the ravages of dementia, of loss and confusion. But, as can happen when we allow ourselves to live fully into the grief and sadness, with full hearts and clear eyes, there is also the beginnings of acceptance, an allowance to let those moments come and be as they will be; and there has always been love—but even that is being felt more deeply now. And as Weller and O’Donohue would remind us, that is SACRED territory. To be given the opportunity to be with Dad at this time of his life, as he is dying, is more profound than even I could have ever imagined.

It’s his gift to me even as he has no idea he’s giving it.

“Grief work is not passive; it implies an on-going practice of deepening, attending, and listening. It is an act of devotion, rooted in love and compassion.” (p. 5)

Like it or not, fear it or welcome it (yes, I think one can welcome grief—even have faith in it, as it always leads to soul—because…), it is inevitable a human life will have ample exposure to grief opportunities. As we’ve seen, how one approaches those moments, mean all the difference in how we approach the entirety of the rest of our lives.

“Without some measure of intimacy with grief, our capacity to be with any other emotion or experience in our life is greatly compromised.” (Weller p. 22)

So, yes, as mentioned, things are more real now. Which is code for—“Dad really is going to die,” and likely sooner rather than later. Though he hasn’t had a second seizure since that episode at the Thanksgiving table (trust me, the irony and grace of that timing isn’t lost on me), there has been a noticeable increase in diminishment (that was well underway before the seizure occurred). Now, Dad is still alive; he’s living, I think, the highest quality of life possible; and he may still have many months ahead of him. But…

Most of the time now Dad is no longer able to walk without direct physical assistance even with his walker (so I always have hands on him on either his hands or his hips for guidance, safety, and support; and because of a near-fall this past week, we will now be using the wheelchair as well in our home); he can hardly stand from sitting on the toilet on his own now; he is having less ability to control his bladder and bowels; and he is less cognitively engaged and “with us” as he is having a hard time holding on to the threads of conversation. He stares off into space for long periods. He often now needs to be directly told to do certain things like stand up, and sometimes more than once (especially off the toilet) and directly in front of his face so that he REALLY hears me, hears the direction. The freezing episodes happen more often, and time is blurring even further for him from the confines of the reality the rest of us hold on to and count on. He tries at times to refuse the taking of his medicines; and he doesn’t eat as much as he used to—his appetite is clearly reduced. (On the medicine issue, know that I was able to talk with him about this and how it is best we make any adjustments like that under the full knowledge and guidance of his doctor. And so we will.) He is sleeping more during the day; his voice is losing its timbre and rigor; his endurance to do anything other than sit is almost nil; and he is having a hard time holding on to memories from experiences and conversations that happened mere moments before. Though he still “has our names,” they are taking just a bit longer to sometimes come from his tongue. Losing our names, I know, will mark another significant milestone in dementia’s progress—for both Dad and for us. And that time is on its way.

The times when he pleads with me to not leave him, not leave his side, to “come right back please” if I go upstairs to use the restroom or prep a meal or wash dishes, are increasing—such is his level of fear, neediness, and uncertainty.

And then some days are better; but who’s to judge that and how is that judged? Judging = more suffering. We don’t need more suffering. And I don’t have the right to judge my father.

Everything, always, is just as it is. It does no one any good to think things “should” be otherwise.

The wisdom of his body might now be starting to wake from his mind’s “death-denying” slumber. It’s a time I’ve been waiting for—it’s a time that one can find trust and have faith in the evolutionary wisdom of the body, provided one knows to do so. Dad didn’t know to do it consciously—so his body, it seems, is now taking the lead much of the time. Right on its own unique schedule.

Yes, things ARE more real now. And also 1 + 1 does = 3; and “this too,” and “reverence in approach,” and “there is only this moment and this moment can be beautiful too,” are ALL more real as well. It’s all a part of the reverence of approach in this, my “apprenticeship with sorrow.”

Grief is just part of the dance.

When we [are] able to see times of loss as inevitable and, in a very real way, necessary, we are able to engage these moments and cultivate the art of living well, of metabolizing suffering into something beautiful and ultimately sacred. It may be strange to imagine grief leading to beauty, but imagine, for a moment, the shining face of someone who has just released his or her cup of tears standing before us naked and cleansed. We are seeing someone as beautiful as Botticelli’s Venus or Michelangelo’s David. (Weller p. 22)

And Dad is a beautiful soul.

things are grey today

and i guess this is to be expected

on a cold, and overcast winter morning.

but still i’ve noticed the color

and it’s not often that i do;

the grey in everything, in higher relief.

am i seeing the grey

now

because of one of the most important

of life truism’s:

“we don’t see the world as it is,

we see the world as we are”?

if so, then i guess i resemble that remark.

in truth, there is grey in my heart just now.

because i have seen too much of the pain

others hold.

i have seen the depth of human emotion

and suffering.

i have seen what one human can do

to another,

what one parent can do

to their child.

what we do

to the earth and the innocent beings.

i have seen grief,

i have seen death.

but I have seen joy too,

which is why I can see in the dark.

in short i have seen humanity.

i see grey

because my heart can feel grey.

and yet grey can be the most beautiful

of colors.

how odd that that is so.

but you have to see it

as you are. And through it all, still…

there is joy.

T plus 159 days…and counting. Grief has descended upon us. Let it nourish our soul to make us more fully human for the benefit of all those who come after us—and who want to learn from our example. There is joy to be found there…

… in Reverence.

It’s a shame that Wally doesn’t realize what a Trooper he is.