Before you read any further, it might be a fun exercise to pause for a brief moment and define hope for yourself. What is the meaning of hope? Why have hope?

Do you live with hope?

Recapping:

My Paradoxical Practice #1 is “Don’t Care.” —> Stop caring about how anything turns out. Turns out, things turn out the way they will no matter our desire to want something different. Better to allow that than suffer for not getting what I want. In Zen language, this approximates “simply bearing witness” to what happens. (Doesn’t mean you can’t or don’t fight like hell for your values though! You’ll see next week.)

Paradoxical Practice #2 is “Doubt.” —> AKA in Zen language: Not Knowing. This is the antidote to hypocrisy. A healthy and constant questioning of one’s own stance as a means of sharpening the edge of Truth. Healthy doubt boils down opinion and belief to foundational facts. AKA evidence of what is true. In doubt lies wonder. And I like to live in a state of wonder.

Now, perhaps the most Paradoxical Practice of them all:

Paradoxical Practice #3: Have No Hope.

Ending Hope

This practice feels much different than the first two—when I was first introduced to the concept of “live without hope,” I thought it asinine, pessimistic, and depressive. “If we do not have hope in our lives, aren’t we left to live a life of darkness, pessimism, fear, and apathy? Without hope, why bother with anything? Without hope, don’t we risk seeing things as hopeless then?”

Not quite, that. See that last sentence there, the one that started “Without hope….” That’s inaccurate. More bluntly, it’s wrong. The sentence should read “WITH hope, we run the risk of seeing things as hopeless.”

With hope, we run the risk of seeing things as hopeless. They are two sides of the exact same coin. You cannot have one without the other. Hope and Hopelessness are a pair.

“We reach for hope as the antidote to despair, but actually hope is the cause of despair.” ~ Meg Wheatley

There is no small amount of nuance to understanding this particular practice, such the paradox that it is. “Having hope” is conditioned into us, all the time, from everyone, everywhere. It is the polite way of responding when bad news arrives: “Okay, so this has happened. Let’s hope for better times now.” “I hope we win next time.” “You feel a lump? Oh I hope it’s not cancer!” “Don’t give up hope!” “We have to give the people hope!”; or when we want good times to continue: “I hope this feeling lasts forever!”; or when we want something we don’t yet have: “I hope Santa delivers this year! I hope I get ___ for my birthday!” “I hope he proposes this weekend!” “I hope she says yes this weekend!”

Heard any of these?

Heck, political candidates even reduce it to a one word slogan on their lawn signs and posters. I guess if they don’t get elected, there goes all hope. Some believed this. Maybe I did too. Two sides of the same coin.

(Hmmm…come to think of it, “If he does get elected, there goes all hope,” works kinda in the same way!)

Anyway, these lamentations on hope all have one thing in common—they rob us all of what the greatest religions, sages, wisdom keepers, and faith traditions teach at their core: to live in the present moment. One way of knowing you aren’t living in the present moment, is when you find yourself with hope.

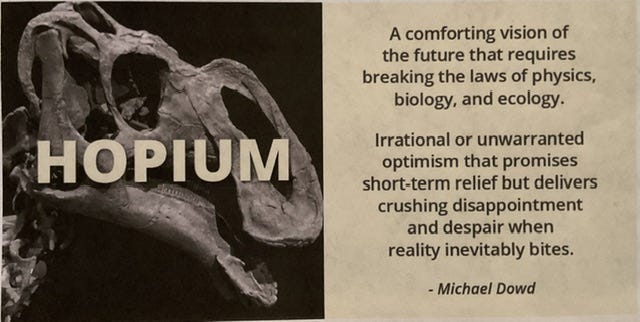

So what’s going on here? The seduction of hope = hopium for the masses

It took a while to marinate in the concept, which allowed me to explore to greater depths what hope is as it is commonly used and felt by most humans, before I started to understand the importance of living a life devoid of hope (hang in there with me! I didn’t say a life full of despair!). As often happens, whenever I dig into spiritual and/or intellectual paradigms, things and people show up in my life that help bring clarity. When it comes to Living Without Hope, I benefitted from the thinking of a diverse group of teachers: the comedian Jim Carrey; deathcare expert and social raconteur Stephen Jenkinson; Buddhist Zen Roshi Joan Halifax; Korean Zen Master Hyon Gak Sunim; the philosophers/activists Rebecca Solnit, Hannah Arrendt, and Terry Patten; Zen Master and co-founder of The New York Zen Center for Contemplative Care, Sensei Koshin Paley Ellison; and author/social anthropologist Margaret Wheatley.

“Many of us consider hope to be a virtue, even a sacred principle, but it is a provocative fact that many of the world’s wisdom traditions disagree about the nature of hope.”

~ Koshin Paley Ellison

We typically use hope as a motivator in our lives, if not a veil to keep us from looking at what is real and right in front of us with all its honesty and rawness. When we’re down, or things aren’t looking good, or even if things are going great and we want that to continue for us, we often turn to hope to motivate. If you look deeper into that realm, you’ll see hope is an empty form of motivation. And, it’s harmful. Because the conjoined twin of hope is fear. Fear that we’ll stay stuck in the down, fear that things won’t get better, and fear that our lucky streak of good won’t last.

“It is important to say what hope is not: it is not the belief that everything was, is or will be fine. The evidence is all around us of tremendous suffering and destruction. The hope I am interested in is about broad perspectives with specific possibilities, ones that invite or demand that we act. It is also not a sunny everything-is-getting-better narrative, though it may be a counter to the everything-is-getting-worse one. You could call it an account of complexities and uncertainties, with openings. “Critical thinking without hope is cynicism, but hope without critical thinking is naïveté,” the Bulgarian writer Maria Popova recently remarked. And Patrisse Cullors, one of the founders of Black Lives Matter, early on described the movement’s mission as to “Provide hope and inspiration for collective action to build collective power to achieve collective transformation, rooted in grief and rage but pointed towards vision and dreams”. It is a statement that acknowledges that grief and hope can coexist.”

~ Rebecca Solnit (quoted in Meg Wheatley’s essay “We have to talk about Hope.” See below for link)

(Bold print mine for emphasis)

Hope as a veil, intentional or otherwise, is actually something more insidious and hurtful to our spirits:

“Hope is a dangerous barrier to acting courageously in dark times. In hope, the soul overleaps reality, as in fear it shrinks back from it.”

~ Hannah Arendt, political philosopher and Holocaust survivor (quoted in Meg Wheatley’s essay—see below)

~~~~~~~~~~~

[Important side note: The late Admirable James Stockdale, during the war in Vietnam, was captured and held prisoner for 8 years (imagine that!) suffering deplorable conditions and regular episodes of torture. Yet, he survived and thrived. His story and survival was actually given a name: The Stockdale Paradox.

So why did Jim Stockdale survive whereas others didn’t? In an interview, he said:

“I never lost faith in the end of the story. I never doubted not only that I would get out, but also that I would prevail in the end and turn the experience into the defining event of my life, which in retrospect, I would not trade.”

He was asked ‘Who didn’t survive?’

“Oh, that’s easy,” he said. “The optimists.” [Those who lived with hope.]

The interviewer pressed Stockdale for more details.

“The optimists. Oh, they were the ones who said [and hoped], ‘We’re going to be out by Christmas.’ And Christmas would come, and Christmas would go. Then they’d say, ‘We’re going to be out by Easter.’ And Easter would come, and Easter would go. And then Thanksgiving, and then it would be Christmas again. And they died of a broken heart.”]

(~ source: learning-mind.com)

There is no need for hope when you live fully in the present moment, even when the present moment is painful—because even then, life is gifting a teaching. You can have faith in that. I live according to the tenet that life doesn’t happen to me, it happens for me. We can want for something different all we want, but hoping won’t make it so any faster—we’ll still be faced with enduring the pain. Hope is a reliance upon a future that will never come and when something of a future does arrive, it is never in the way I imagined or even necessarily worked for. Hope is a desire, and having desires are invitations to suffer. Want to suffer? Fine, desire for something—hope for it to come true for you. See how you feel when your desires aren’t met. When your hopes are dashed. FULL DISCLOSURE TIME: I had a pretty MAJOR desire on November 5, 2024. And what I wanted didn’t happen. Suffering ensued, in a BIG WAY! I’m not perfect at these practices—so I make sure to practice more. And you know what, they help. A lot, they help. I’ve adopted into my life a profound outlook expressed, ironically, by the comedian Jim Carrey:

“And when I say, ‘life doesn’t happen to you, it happens for you.’ I really don’t know if that’s true. I’m just making a conscious choice to perceive challenges as something beneficial so that I can deal with them in the most productive way. You’ll come up with your own style, that’s part of the fun!

“Oh, and why not take a chance on faith as well? Take a chance on faith — not religion, but faith. Not hope, but faith. I don’t believe in hope. Hope is a beggar. Hope walks through the fire. Faith leaps over it.”

Hope takes me out of the present moment—and there is nothing I want more than to be more fully present in this present moment. Faith says I’ll get through the present moment better for having lived it fully. If I’m thinking about being elsewhere, I’m not fully here. And that robs me of the gifts that this present moment could give me.

“Hopeful people generally have their one good eye on the future they imagine, the more jaundiced eye on a present they mostly tolerate, and both eyes on a past they have a hard time remembering well and letting go of. Hopeful people do not as a rule hope for what they [presently] have. They hope for what they do not have. They hope for what they once had to come again. Hopeful people do not in their hopefulness often vote “yes” to the present. They vote for a future. Even those with a greater agility of hope, who hope for more of what they have, they are still voting for a future in which to have it.”

~ Stephen Jenkinson (p. 132)

One of the ultimate facts in this life is that no one has a right to, or guarantee on, any future. It could all end tomorrow (on average, for about 150,000 people alive right now, it is a matter of fact they won’t be tomorrow).

Where, then, goes hope?

“We are all terminal patients, every damn one of us. We are all in the same existential boat, no special escape. No one has any guaranteed length of time left for themself. We only have Moment. Moment. We can lie to make a ‘hope’ for an imaginary future, or we can have real hope right in this Moment. True Moment has no ‘me,’ has no ‘you.’ True Moment has no ‘Buddhist’ or ‘Christian.’ Has no ‘I have time,’ ‘You have no time.’ Moment is infinite time and infinite space—this ‘moment’ is the very thing Jesus spoke of when he talked about giving us ‘eternal life’ — there is no other meaning, no other life than this moment.”

~ Hyon Gak Sunim

Being Hope-free

“Hope is very often a refusal to know what is so, and steadfastly, it is a refusal to live as if the present moment is good enough and all we really have. Hopeless is the collapse of that refusal, and it looks a lot like depression. The alternative is to live your life and your dying ‘hope-free.’ [Living] and dying hope-free: that is a revolution.”

~ Stephen Jenkinson

The fact is, the present moment IS good enough because it is all we ever have. And it can be made to be much better than just “good enough” because we can MAKE it so. If the present moment is not to your liking, hoping it will be different is throwing all your agency out the door, “hoping” some one (God? Santa? Mommy?), or some thing (Chance? The Lottery? My inheritance money when mommy dies?) will come to the rescue of this lamentable moment to grant us our wish and desire. But life, reality, and nature never work that way. No other animal, or organism of any kind, other than humans, lives with hope, or needs to. Humans don’t need to either. So when you think about it, like regret and guilt, hope is a worthless emotion because having hope makes us a powerless begger for something we don’t have and likely won’t get.

Jenkinson again:

“As long as you are hopeful, you are never in the land you hope for.”

Putting all one’s coins in the hat of hope relieves one of the power and responsibility one should never give up to make the moment different. Humans DO have agency to bring about something different—but the only way that works, is to make the necessary choices in life right this moment that MAY lead to a new, more desirable yet not guaranteed, outcome. But even then, as Paradoxical Practice #1 states, we are not meant to care about outcomes because when we do care, we open ourselves up to suffering. Is it becoming clearer how each of these three paradoxical practices work in conjunction with each other? They all are of a piece: Don’t care, doubt your beliefs, have no hope. On the surface they sound gloomy—but that’s the point. That is why they are paradoxical—because they serve as the stark reminder that reality is real, and that nature just is the way it is (there is pain and injury and death along with joy and healing and birth). Below the surface level perceived feeling tone lies a sense of openness and freedom that usually goes untapped for people who do care about outcomes by becoming emotionally attached to them; by people who never doubt their beliefs, despite sometimes overwhelming evidence to the contrary; and by people who live with hope thus giving up ownership over their own agency to effect positive change. If you indeed do act to effect change, what purpose does hope serve then? Hope is not an essential ingredient for success or a better future. See???

As Stephen Jenkinson states, we, as a culture, like to live in the binary lands of “this OR that.” One or the other. If faced with the binary choice of “hope or hopelessness,” who would actively choose hopelessness? Not me! But this is NOT a binary choice—and this underlies the whole Paradoxical Practice: having no hope does not mean I am then relegated to living a hopeless, despairing life. Quite the contrary. “Living and dying ‘hope-free’ is revolutionary.” It prompts me to ask myself in every moment in which I might want to hope for something, “what can I DO right now to create a different future moment from the one this present moment seems to be aiming toward?” This is NOT about praying (which is just another worthless form of hope); for me, this also isn’t about a doing, contrary to what I just wrote. As next week’s post will state as a closure to this Paradoxical Practices series, this is truly about a Way of Being. About having faith in a specific way of approaching life that 100% guarantees a life of satisfaction, understanding, joy, and equanimity.

Our, well…my spiritual growth has been to see this present moment as it actually is and to accept it fully no matter its impact upon me personally. There is no other alternative to hope for, because this reality will always be exactly as it is. How do I know this? Because this reality is exactly what’s here. No one can have a different present moment from the exact one being experienced.

Living a life devoid of hope is actually living “hope-free.” To me, that is an empowering statement—and I like to feel empowered. So, this Paradoxical Practice of “Have No Hope” is a life-affirming, powerful, and empowering practice. It has informed my being such that, when encompassed under the greater umbrella practice that I’ll share next week, frees me from the tyranny of hope as the waste of energy it is. I’ve even excised from my vocabulary seemingly innocuous uses of the word hope in casual conversation: e.g. “hope you have a good day,” “hope you enjoy the concert,” “hope it stops raining soon,” “hope you get that raise.” But I’m not a Debbie Downer; in fact, I doubt anyone else has even noticed I rarely use “hope” in conversations. My language reflects a greater sense of empowerment—at least that would be my intention. And THAT, I think, others do sense.

As Meg Wheatley writes: “The antidote to despair is not hope, it is love—love for the beauty and harmony of life even as we despair for the destruction caused by us humans.” I believe the next four years will offer us much as a means of entrapment into the dark depths of despair. The antidote to the next four year’s worth of experiences and present moments is not to be built on the hope for a better future, but on the love for the values we hold dear coupled with the effort we must join together to manifest so that a more life-affirming and compassionate world can result. In. Each. Moment.

Next week, I aim to tie all this together for no one else but for my own thinking and journey as I reflect upon the Alchemy that is my life. All this has been my opinion and my opinion only. If you found any truth or benefit in any of it, it is only because you have experienced something that resonated, something that was true for you.

I could hope for nothing more.

Live, Laugh, and Love—with Clear Eyes and a Full Heart.

Always and Ubuntu,

~ kert

Ahimsa!

🙏🏼

Works cited:

Jenkinson, Stephen. Die Wise: A Manifesto for Sanctity and Soul. (North Atlantic Books, Berkley California. 2015)

Jim Carrey: see his entire, superb Commencement Address here, or a highly recommended, wonderful YouTube video here.

Solnit, Rebecca. Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities. (Haymarket Books, 2016.)

Stockdale, James. In Love and War: The Story of a Family’s Ordeal and Sacrifice During the Vietnam Years. (US Naval Institute Press, 1990)

Roshi Joan Halifax’s essay: Yes, we can have hope.

Hyon Gak Sunim’s essay “Buddhism Has No Hope.”

Koshin Paley Ellison’s Substack essay: Hope is a plague. What is a path of freedom?

Margaret Wheatley’s essay: We Have to Talk About Hope

As Ben Franklin said "If you live on hope you die fasting." Great insights in the post, thank you!

This is a wonderful post, Kert. Its message felt very close to a part of Chapter 2 of the Tao Te Ching for me.

“Therefore the Master

acts without doing anything

and teaches without saying anything.

Things arise and she lets them come;

things disappear and she lets them go.

She has but doesn't possess,

acts but doesn't expect.

When her work is done, she forgets it.

That is why it lasts forever.”

Which is a way of being I work to live by. As you say, sometimes it’s easier than others.

I’m interested to know how you don’t use “hope you…” in interactions. As soon as I started reading this I thought about saying “I hope you’re doing well” to people when I message them.