…with a lifetime of memories between. And still.

Yesterday, September 12, 2024, would have been my Dad’s 86th birthday—31,412 earth rotations on those 86 solar orbits. That’s what would have been. My dad ended up living 30,865 days. Minus those 254 days above, my Dad spent his entire life living in the Yakima Valley—virtually his entire life living the identity of a farmer. He had lived in many houses in the Valley over those years: houses in Moxee, Union Gap, Toppenish, back to Moxee, then two homes in Terrace Heights, and then into an Adult Care Facility in Yakima when his health proved too challenging for him to live safely or with our dear friend (and adopted family) Pat. Although we wanted him to thrive in that Yakima facility, we knew he wouldn’t. That was the last thing Dad wanted even when, at the time of our decision-making, he understood the reason. Soon enough, it became even too much for us to bear—seeing his deterioration and his sadness. So, we pivoted—we changed our family situation to make things better for him. Turned out, it was better for all of us too: in ways expected and unexpected.

Transitions

On July 4, 2022, my family brought my Dad across the Cascade Mountains to live with us for what we knew, and intended, was going to be for the end of his days. One hundred fifty miles away from the places he had always called home; to our place that he eventually also came to call home—although I do sometimes wonder if he really felt truly comfortable here. The comfortable that only comes when one is truly home. My dad loved and missed Moxee; he loved and missed farming. Farming WAS his life.

But, he loved it here with us, too. He was where he wanted and needed to be: with family; safe, cared for, loved, fed (he came to love the vegan lifestyle even though he NEVER knew we had turned him into a vegan!), and did I say loved?

When we moved him in, we did so with a huge “not knowing” in front of us. We did not know, even though he was diagnosed with Lewy-body dementia, Parkinson’s, and congestive heart failure, how many days, weeks, months, or even years might be ahead of us. Even when we placed him under the care of a geriatric physician here, and even when we enrolled him into Hospice, we did not know what was still ahead of us. It’s so tempting to ask the doctor “how many days do you think he has left,” but doctors have no real idea. Their guess, and granted it would be an informed guess, would have been no better than the guesses we could have made. But, we didn’t guess and I would have never asked the doctor that question anyway. Because, it didn’t matter. And it doesn’t matter. Until my dad died, he was living. And our mission to live each day as fully as possible remained, even though it lasted only 254 days.

IDPs

There comes a moment in time when the Hospice care team makes the determination to place the patient on what is called “Imminent Death Protocol.” Things change just a bit in the patient’s care—and for their family too. Members of the team may visit more often, if not daily, to insure the patient remains comfortable, pain and stress free to the greatest degree. The team can also assess and support the family caregivers as well to provide them with information and knowledge of what to expect as the body continues its shutting down. The team insures the patient and family have ample supplies and the necessary prescribed medications, with directions on their use, if that was a part of the patient’s wishes for end-of-life care.1

My Dad wasn’t in Hospice care for long (which is very typical in our country). And to be honest, I’m not sure if the team placed Dad under an IDP. I want to believe, and do believe, that was because of the exceptional care we were providing him and the support and love we were giving each other. I’ve said, even in this Substack place before, that our culture does not “do death” well—in all realms: physical, social, emotional, psychological…and even spiritual. We are living proof a death can be done very well. Very well indeed—to the point that, 547 days since his death, on what would have been his birthday, I think most in Dad’s family would agree we gave Dad a beautiful death. Or, maybe more accurately, he gave us his beautiful death.

A brief aside, but maybe the main point I wanted to get across today: do you see the folly in a formal IDP?

We ALL are living an imminent death—in each moment of our lives. We forget that, don’t we. It’s a spiritual and mindful practice, as the Tibetan lamas teach us, to live with our own deaths firmly in mind. It is said that in doing so, we make our end something that can be calm, loving, and welcoming. Even beautiful.

I wonder often, if we remembered more often that an IDP is actually our daily living, if we’d:

Fight each other less,

And love each other more.

Throw less punches and arrows both actual and metaphorical,

And hug each other more.

Initiate less war,

And spend our energies finding and living in peace.

Buy less guns,

And more roses.

Put up less walls,

And erect more gates and bridges.

Build less armaments of violence,

And more parks, and schools, and open spaces of nature.

Accumulate fewer enemies,

And more friends.

Ignore each other less,

And help each other more.

Tear down less forests,

And plant even more trees.

Drive less,

And walk more.

Say I hate you less,

And I love you more?

The protocol for an imminent death is a life well-lived.

Shouldn’t that be our forever IDP?

I think it actually was for Dad—his forever IDP, his life well-lived, was one of kindness. No one was ever able to find a mean bone in Dad’s entire body. Because there wasn’t one. But even so…

One of the reasons Dad needed to be with us through his dying was because we knew Dad wasn’t going to do his death well. He was scared of all the typical unknowns (eg pain, lack of bodily control and autonomy, how to say goodbye, how to miss us, what happens the moment after the last breath, and each moment after, etc). There would be a few quiet times when Dad got sad to the point of tears. He was sharing his fear with me and so we’d talk about that. Ultimately, what gave him the greatest amount of peace, was to reassure him we didn’t have to worry or concern ourselves how things would be in the future—we just needed to live with love now. I kept reassuring him we would never leave him (and we never did!), that we would keep him pain-free, comfortable, warm and clean, and that he was always loved just as he would tell us he loved us. My Dad was a man of faith (of the Catholic brand); he prayed privately to himself every day. And even though he stopped going to Church a few months after my mom died, I believe he still had faith in the existence of his God. One of the privileges of living these days with my Dad was knowing we were living huge, existential moments. Moments that were deeply Soulful.

I honestly don’t know if there came a time where Dad knew he was very close to dying. Yes, he knew it was on his horizon, but I think he was still wanting more days. And then more days and weeks after those, even. One of the things I kept reassuring him, when he was confused and fearful of what was coming, was that, indeed, we didn’t have to have the answers because his body knew how to do this. Our minds may be confused and scared, and hearts may be grieving, but our bodies have the ancient wisdom of death built in. No other organism resists death like the human organism can. If we know this, and trust the wisdom baked into our bodies, maybe we can make our own deaths, do our own deaths, in ways unexpected and beautiful in their own right.

“Tibetan Buddhism teaches a lot about the transition. As we approach death, the five elements that formed and sustained our bodies begin to dissolve (and this is true each and every time outside of a traumatic and sudden death): earth, air, fire, water, and space. [All the elements that make us, us.] When the body begins to lose strength and feels drained of energy, when we feel like we are falling, sinking, and become weak and frail, the earth element is withdrawing. When we begin to lose control of bodily fluids, the water element is dissolving. When our mouth and nose dry up, when all the warmth of our body begins to leave and the breath is cold, when sound and sight are confused, this is the fire element dissolving into air. Then, when it becomes harder and harder to breathe, the air element is leaving. When the element of space withdraws, mind consciousness dissolves and breathing stops. We are returning to our original state, our true nature. Soul.”

(From “Walking Each Other Home: Conversations on Loving and Dying” by Ram Dass and Mirabai Bush.)

My Dad followed this exact pattern. I know. We were there—alongside each step at the end of his journey, just like we promised, bearing witness to the dissolution of each of his five elements, until we parted when his Soul continued on, leaving his body, and us, behind. We gave him permission to let go—sometimes it’s important to do that, for everyone.

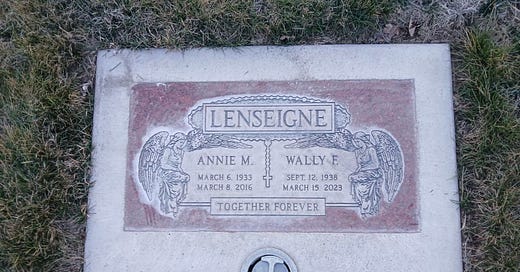

My brother and I bathed Dad’s body one final time with lavender-infused soap and water. We dressed him in his favorite polo and comfy sweatpants. We covered him in a blanket and spread rose petals atop. And we placed mom’s rosary in his hands. Then, at some point later, we returned him to the earth—on the land he proudly farmed. The place he called home all his life. The place he loved—alongside mom’s cremains. And there they will stay, until at some very distant point, the earth does it’s work to dissolve even all that.

Five hundred forty-eight days into a world without Dad among us, physically present, has us still marking his milestone dates—the day he died, the day he moved in with us, the day mom died, the day of their anniversary, and the day he was born—September 12, 1938. We carry Dad forward in our hearts—and every time we are together, we tell stories. So, Dad’s not “dead,” yet. We still remember, and we still keep him alive in a more intimate place than he ever was when he was alive in body and living only on his farm in Moxee Washington—he’s now everywhere we are, no matter where we are.

And that’s a pretty cool and beautiful thing.

We love you Dad. And we know you’re listening.

Live, Laugh, and Love—with Clear Eyes and Full Hearts,

Always and Ubuntu,

~ kert

And with Ahimsa!

🙏🏼

PS: Two posts, two hundred fifty-four days apart.

The first ‘Stack with Dad with us:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The first ‘Stack following Dad’s death:

One of the BEST things you can do for yourself, but more importantly for your family (it is a TRUE gift), is to complete what is called a POLST—Physician’s Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment. These are Advanced Directives, in a simple written document you keep handy in your home, made with your physician’s approval, that tells health care providers and first responders how best to treat you when/if imminent death may be near. My wife and I have completed a legal document called “Five Wishes.”

Anyone, at any age, can have a POLST—and, in my opinion, should. Having these important conversations ahead of time, with your family, provides vital guidance at a potentially traumatic and emotional time. It’s for peace of mind (yours and your family’s) to have at the ready your wishes for how you want to be treated when you might not be able to communicate at all. My Dad had an up-to-date POLST—and we followed it to the letter. We gave Dad exactly what he wanted—and that has been a source of pride and great comfort to us.

Here are two great resources that provide information on Advanced Directives:

Such a lovely thing to say—if you knew my dad, you’d have loved him too. Such a kind and gentle soul.

Have fun with grandmunchkinson this weekend!

This is really wonderful Kert. Thanks for sharing this experience with us. Your father seems like he was a wonderful man and I am glad you had the chance to share that time with him.